-

3-minute read

-

2nd July 2016

Independence Day (The Language of the Declaration of Independence)

Happy Fourth of July! 240 years ago today, America’s founding fathers agreed to adopt the Declaration of Independence (it wasn’t signed until August). Traditionally, we mark Independence Day with food, flags, and fireworks. However, we’re proofreaders, and there’s only one way we know how to celebrate: pointing out grammatical and spelling mistakes. Today, then, we shall turn our pedantry towards the Declaration of Independence to see how our language has changed since 1776.

Capitalization

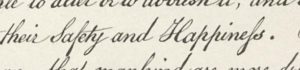

Anyone who reads the Declaration of Independence will notice that some words are capitalized when you wouldn’t expect them to be. Sure, there are some comparisons with modern English, like capitalizing “Government” when referring to a specific government. But others, like in “Safety and Happiness,” are less familiar. However, this capitalization was a common way to emphasize particular words at the time, so it only seems odd to modern eyes.

American vs. British English

American and British English have since developed in different ways. In 1776, though, British spellings were dominant in America. We can see this in the Declaration of Independence with the spelling of “neighbourhood.”

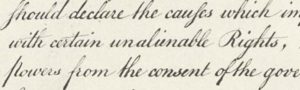

Another example is the use of “which” and “that.” The British still use these terms interchangeably, but American English uses “that” for clauses that change the meaning of a sentence (restrictive relative clauses) and saves “which” for clauses that simply add more detail (non-restrictive relative clauses). But the Declaration of Independence uses the British model.

An interesting exception is the last word of the document, “honor,” which uses the modern American spelling rather than the British version (“honour”).

Other Spelling Issues

There are also some unusual spellings that we can’t blame on the English, like “compleat,” “hath shewn” and “Brittish.” And don’t even get us started on the inalienable/unalienable thing. That one is just confusing.

In reality, we can’t call these “mistakes,” since it’s only recently that many spellings have been standardized. But they still look strange to our eyes.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Subscribe to Beyond the Margins and get your monthly fix of editorial strategy, workflow tips, and real-world examples from content leaders.

Gendered Language

That “all men are created equal” is one of the most famous lines in the English language. But the fact it says “men” reflects how women were excluded from public discourse. Nowadays, we’d probably pick a more inclusive term.

We’d hopefully also reconsider the reference to “merciless Indian Savages,” which could sound ever-so-slightly insensitive these days.

A Very Important Period

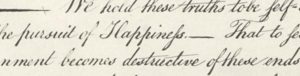

We won’t go into depth, but some scholars think we’ve been reading the Declaration of Independence wrong. And this is all because of a misplaced period after “the pursuit of Happiness.”

Put simply, the use of “That” at the start of the next sentence suggests it was supposed to run on from the previous part, while the period is also missing in some versions of the document.

The issue at stake is whether the following passage – related to how governments are instituted to protect the rights of citizens – counts as one of the “self-evident” truths that precede it.

If nothing else, it’s definitely a good example of why proofreading is important!