- 4-minute read

- 5th November 2019

Gunpowder, Treason and Plot: The Etymology of ‘Guy’

The 5th of November is Bonfire Night in the UK, a time for lighting fires, burning human effigies, and watching things explode. And, oddly, this celebration shares an origin with the everyday word ‘guy’.

So, where did Bonfire Night come from? And what has it got to do with the word ‘guy’? Let’s wrap up warm, grab a sparkler, say ‘ooooh!’ at the fireworks, and look at the where the word ‘guys’ comes from.

What Was the Gunpowder Plot?

While it is now a family-friendly celebration of pyrotechnics, Bonfire Night began as an attempted political assassination. It is, in that sense, a unique annual festival (unless Santa has a darker history than we know).

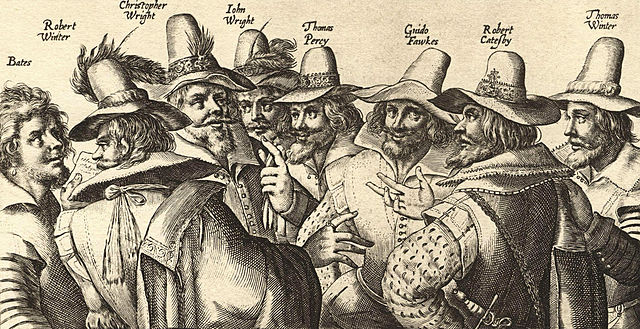

To expand on this a little, the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 was a failed plot to kill King James I by blowing up the House of Lords while he was there for the State Opening of Parliament. Although many people were involved in the plot, the name most people know is Guy Fawkes.

Fawkes’ fame comes from being caught guarding 36 barrels of gunpowder on the 4th of November. He was then found guilty of high treason and sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. In the end, Fawkes died from a broken neck after jumping from the gallows. But his body was quartered, with each part displayed in part of the kingdom to warn against uprisings. Fun, eh?

The next day, bonfires were lit to celebrate the plot being foiled. And this later became an annual event on the 5th of November, with fireworks becoming a staple by the 1650s. But another common Bonfire Night tradition is the burning of the ‘guy’, named after poor Guy Fawkes.

Burning Human Effigies?

Okay, we’re done with the plot. But we still have the question of how it eventually led to the word ‘guy’ (meaning ‘man’) that we know today.

The answer to this lies in the ‘burning of the guy’ mentioned above. The ‘guy’ in question here was a literal effigy of Guy Fawkes, as captured in this slightly bloodthirsty nursery rhyme from the 1870s:

Remember, remember the fifth of November,

Gunpowder treason and plot.

We see no reason

Why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot!

Guy Fawkes, guy, t’was his intent

To blow up king and parliament.

Three score barrels were laid below

To prove old England’s overthrow.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

By god’s mercy he was catch’d

With a darkened lantern and burning match.

So, holler boys, holler boys, Let the bells ring.

Holler boys, holler boys, God save the king.

And what shall we do with him?

Burn him!

And burn him we have! Many times, year after year. But burning actual humans is now frowned upon, so the ‘guy’ burned on Bonfire Night is an effigy, usually made of old clothes stuffed with straw or newspaper. This poor creation is then sacrificed to the flames on the 5th of November.

In British English, then, ‘guy’ became a word for these effigies. It then later become an insult for a scruffy or poorly dressed man, but it lost this negative connotation in American English. And since then, the word ‘guy’ has become an informal word for ‘man’ or ‘person’ in general.

From Guy Fawkes to ‘Hi, Guys!’

These days, people use ‘guy’ to refer to a man without thinking twice:

He was a good guy, but he fell in with a bad crowd.

A ‘guy’ can also be a guiding rope, like the ones that fasten a tent to the ground. But this definition comes from the French word guie, meaning ‘guide’, not from Guy Fawkes, so these ‘guys’ are unrelated.

Regardless, it’s interesting to think how the name of a wannabe revolutionary has evolved over the years into a completely mundane word for ‘man’ that we see in writing and hear in speech all the time.

And next time you greet your friends by saying ‘Hi, guys!’, remember that you’re actually saying ‘Hi, failed political assassins!’